The last six or seven weeks have been extremely busy for me, with business travel, social engagements, college basketball, and other activities filling up my calendar. Added up, these events have left me just barely enough time to upkeep a regular schedule of film viewing. And although I've maintained my screening schedule of about 12 to 15 movies per month, only a few of these films have I seen completely through on one viewing. I find myself starting a movie after 9:00 or 10:00 PM more often now, which I used to do quite frequently a couple of years ago. The difference between now and then is that I would last through a whole movie back then. Now I find myself watching a movie in halves or thirds much more, which is acceptable --even useful-- on second or third viewing, but not ideal for a first viewing.

The last six or seven weeks have been extremely busy for me, with business travel, social engagements, college basketball, and other activities filling up my calendar. Added up, these events have left me just barely enough time to upkeep a regular schedule of film viewing. And although I've maintained my screening schedule of about 12 to 15 movies per month, only a few of these films have I seen completely through on one viewing. I find myself starting a movie after 9:00 or 10:00 PM more often now, which I used to do quite frequently a couple of years ago. The difference between now and then is that I would last through a whole movie back then. Now I find myself watching a movie in halves or thirds much more, which is acceptable --even useful-- on second or third viewing, but not ideal for a first viewing. With that said, I have seen several late 2007 movies on DVD; some wonderful (The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Helvetica, Syndromes and a Century), some good (The Darjeeling Limited), and some mediocre (I Am Legend, Lust, Caution). But it's been nice to catch up on some of the 2007 releases I've missed in theaters, especially as I begin thinking about my upcoming Cinema 2007 post.

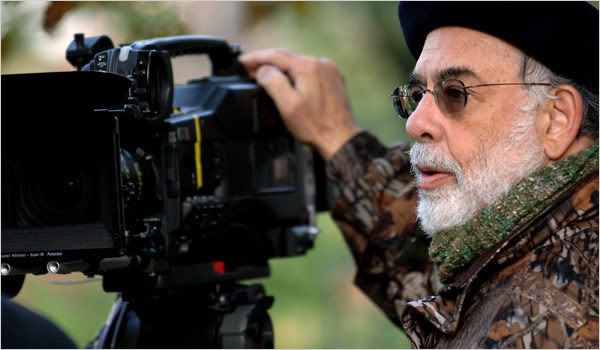

Fortunately, I've also had a few moments to counter all of these current films with a few older treasures (by comparison), which I've seen for the first time. One of these gems is Peter Jackson's famous low-budget horror film, Dead-Alive, one of the most delightfully twisted movies I've seen in some time, and a perfect movie to watch after 10:00 PM on a weeknight. It's is a pure joy from both a comedy and a horror standpoint, and its self-conscious nods to genre favorites are great for fans of the genre. And it's worth noting that the third act may boast the grandest orgy of violence these eyes have seen. So much I enjoyed the film that I couldn't resist posting the picture above (from the end of the film), featuring a lawnmower-wielding lovelorn hero ready to mow his way through legions of zombies. After the recent crop of serious zombie flicks, it's nice to look back on one with a bit more of a comedic approach to the irresistible sub-genre.

-----------------------------------

These excursions into cinephile indulgence that have given me reprieve from the busyness of other time-consuming activities. Apart from these film viewing experiences and other events, I've experienced a number of computer problems, which has severely handicapped my ability to write or post a new entry. So even though I've been able to somewhat maintain my film watching, my reading and writing has taken a hit.

Alas, my frustrations have finally paid off, and I'm coming to you now from a brand new computer with all kinds of new features. (Who knew that new versions of Microsoft Word would include a feature for writing blog posts!) I'm still trying to work out the kinks with adapting to the new system and to Vista, but now that I am up and running I can at least plunge head first into all the blogs I've only been glancing at here and there in recent weeks. As my familiarity with the computer grows, and the rest of my schedule begins to settle down (hopefully), I expect to be more active on the blogging front. But before I dive into some more elaborate and focused posts, I'd like to share just a few thoughts on blogging, from both inside and out.

In the past few weeks, I've only managed to visit web sites and blogs on a sporadic and limited basis. But since I've set myself up with the new computer, it's been refreshing to jump right back in to all the fun. One thing I've learned from being away from the film for a short time is that it moves very quickly. There is so much to catch up on. Perhaps Peter Bart wasn't too far off when we referred to bloggers as "busy bodies," because there is so much activity among film blogs that it's hard to streamline any of it. So much of our own material is rigorously controlled and always changing. We are the gods of our own universe, changing posts content and visual interfaces at will, shifting the entries on the all important blogrolls, and moderating the comments following our posts. Millions of threads of discussion are sprouting in new and old places that to try to jump in is like awkwardly trying to join a race already in progress. One just feels out of place. But when Big Events happen, the explosion of discourse is almost overwhelming (in a good way).

A great example of this would be the recent news that Nathan Lee was laid off by the Village Voice. Some of the discussion that's come about on various blogs has been incredible, reminding me of why I love this medium to begin with. But as Matt Zoller Seitz bittersweetly reminds in a comment over at his blog, The House Next Door, blogging as criticism will likely not be defined as the next step.

"What we're seeing here is the passing of a notable and vibrant phase of movie writing. It'll be replaced by something else, yes, but something very different.

I think we're fast approaching the point where criticism will become, for the most part, a devotion rather than a job.

I'm not quite sure what to make of that. There are definitely a lot of hack-y film critics (and there always have been). But some of the great ones that came along during the era of newspapers and magazines could not have reached a national or international audience without the support of a paycheck, editors, and the rest of the superstructure that professional publications have in place. And that's still true. The best film blogs are influential within the context of the film buff community, but the fact is, on their best days, even the biggest independent, halfway serious film blogs don't have a fraction of the readership of blogs that are attached to advertiser-supported big media outlets.

Will that change as the print medium dies out and becomes mulch for the next phase of journalism?

I wish I knew the answer to that."

While the explosion of online film discourse likely signal the dawn of a new movement in film criticism, as Matt remarks, its lack of structure and tangible direction demonstrates its somewhat perishable nature as well. Ultimately, all this blogging from the variety of professional and non-professional writers alike may not amount to much (in the professional sense), but I'm glad to be apart of it as a reader and a contributor. And as many have already said, hardly any of us have a clue where this little experiment is headed. But maybe that is what keeps us compelled to do it.

------------------------------------

On to some matters regarding TCA:

As I noted above, I will be posting more regularly in the near future. Many of these posts, at least for the next two months, may coincide with a project I'll be working on, which, ironically enough, will look at film criticism and new media in the digital age, specifically exploring the problematic binary of analog / digital and its constraining approach to engaging and understanding the role of new media in cultural and critical discourse.

This project will dominate the bulk of my free time until the end of the semester, but I will also reflect on some other topics in film criticism and on the blogging circuit. I may even post the occasional movie review. But I'm still struggling over how much I should indulge in my own cinematic tastes and experiences, as opposed to providing more currently relevant commentaries. Ideally, I don't want to be reactionary or inconsequential, which is a struggle for all of us "non-professional" bloggers, but it's something worth pondering reflexively as I attempt to gain a kind of critical relevance as a blogger. But if I want to build a solid critical relevance, that means engaging other media and critical outlets outside this blog, both online and in print. Coming months will determine what these endeavors may bring.

For now, however, I have some pieces in the pipeline that should give this site the boost it needs. I'll be presenting a piece on my favorite movies of last year, and will also be offering long-delayed thoughts on my presentation at SCMS.

As always, thanks for reading (and feel free to comment!), to those who take the time.