In the opening scenes of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, we are cued on multiple occasions to swell up in nostalgia for a sense of old-time moviemaking that even the filmmakers seem to think is dead. In the very first shot, director Steven Spielberg wastes no time to make a joke out of the established tradition of the Paramount logo dissolving into the film's opening shot. We think we're looking at a mountain, which turns out to be quite different. From there, the opening title sequence begins with the same letter font that was used for Raiders of the Lost Ark and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. After the title sequence, Indiana Jones makes his "grand" return to the screen with the famous Raiders March performed triumphantly in spite of the downbeat circumstances of his situation. Even when the action begins (in the warehouse from the end of Raiders), the filmmakers can't resist allowing us a small look at the lost ark. These pinch-yourself moments remind viewersm and remind them again that they are in for a trip down memory lane. But with the film resolutely and insistently banging the nostalgia drum every moment it can, the feeling that it is a true Indiana Jones film often seems manufactured.

In the opening scenes of Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, we are cued on multiple occasions to swell up in nostalgia for a sense of old-time moviemaking that even the filmmakers seem to think is dead. In the very first shot, director Steven Spielberg wastes no time to make a joke out of the established tradition of the Paramount logo dissolving into the film's opening shot. We think we're looking at a mountain, which turns out to be quite different. From there, the opening title sequence begins with the same letter font that was used for Raiders of the Lost Ark and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. After the title sequence, Indiana Jones makes his "grand" return to the screen with the famous Raiders March performed triumphantly in spite of the downbeat circumstances of his situation. Even when the action begins (in the warehouse from the end of Raiders), the filmmakers can't resist allowing us a small look at the lost ark. These pinch-yourself moments remind viewersm and remind them again that they are in for a trip down memory lane. But with the film resolutely and insistently banging the nostalgia drum every moment it can, the feeling that it is a true Indiana Jones film often seems manufactured.This mood hangs over the fourth installment in the popular action-adventure series. It's as if Steven Spielberg and George Lucas are winking at us, expecting that we will simply play along in their harmless revisiting of an old friend. Lucas has openly stated that the film is "just a movie," which is no doubt true, even if the marketing campaign would convince you otherwise. Lucas has also said that the film is like the previous films; but this statement is only half-true. While Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull embodies the Indy mood and style to a tee, it also strains to imitate the previous films, rather than fully embracing the energetic spirit of this kind of storytelling. The other films --at least the first two-- worked partly because they delved so deeply and unashamedly into absurdity, reveling in seemingly ancient filmmaking and storytelling conventions. They were travelogues through movie sensations that were made with full conviction, whereas Crystal Skull is far too self-conscious to build and sustain its own rhthyms.

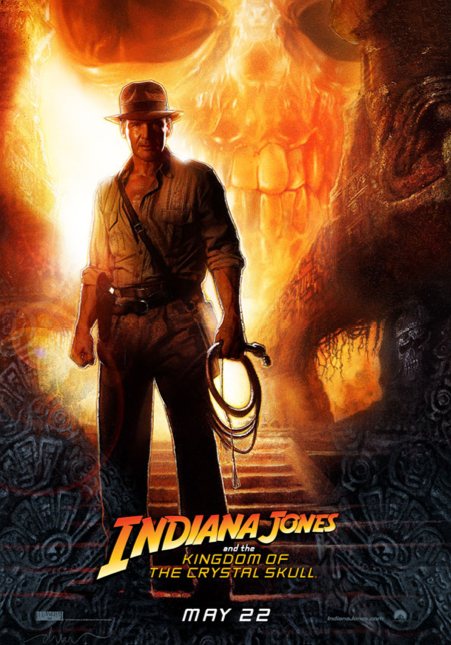

That said, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull still boasts a few moments of pure, unfiltered energy. These inspired bits surface in small places and throwaway sequences, such as in scene transitions, stagings of dialogue, and less than big moments during action sequences. An early example of this is during the extended opening sequence, after Indy escapes from the Russians and makes for a small town in the middle of the Nevadan desert. The vision of an aged Jones -- donning his iconic, unchanged getup of brown slacks, a fedora, and a whip-- running frantically through a sunny, colorful suburban town is a stroke of brilliance. The sequence culminates with a silhouette of Jones foregrounded in the corner of a shot pulling up to reveal a massive mushroom cloud in the background. This play against expectations establishes a harsh contrast in setting and mood that pulled me right into the narrative even more than the sound of the whip cracking in the warehouse scene.

Following these scenes, we return to Marshall College, where the Red Scare has invaded campus grounds. With the constant reminders of the Cold War affecting academia, it's oddly welcoming to return to the classroom and see Indy teaching. Although archeology remains dictated by the same principles, it's obvious that in spite of his love of archeology and adventuring, Indiana has changed. During these expository scenes, the film sets up the main plotdilemma in two ways: First, by establishing the Russians as a collective force and threat, as Indy is dismissed from teaching duties due to a suspicion of his national allegiance. This is an interesting plot device that sets up the remainder of the film rather beautifully, especially since it brings together Indy's absence of place in the world. The next plot push, however, is not as successful. Spielberg and screenwriter David Koepp bridge the two plot shifts in a beautiful sequence where Indy gets on a train leaving town. In just a few economical shots, we go from feeling Jones' estrangement from the world --with train smoke billowing in the background as a solemn version of the Raiders March going through what seems to be its last, dying statement-- to the introduction of Mutt Williams, a la Marlon Brando in The Wild One, who glides into the film as if to remind that there's a story to tell. Before Indy takes off on the train, Mutt informs him that an old professor of his (and friend of Jones) is missing. This is the basis of the film's real plot hook.

Following these scenes, we return to Marshall College, where the Red Scare has invaded campus grounds. With the constant reminders of the Cold War affecting academia, it's oddly welcoming to return to the classroom and see Indy teaching. Although archeology remains dictated by the same principles, it's obvious that in spite of his love of archeology and adventuring, Indiana has changed. During these expository scenes, the film sets up the main plotdilemma in two ways: First, by establishing the Russians as a collective force and threat, as Indy is dismissed from teaching duties due to a suspicion of his national allegiance. This is an interesting plot device that sets up the remainder of the film rather beautifully, especially since it brings together Indy's absence of place in the world. The next plot push, however, is not as successful. Spielberg and screenwriter David Koepp bridge the two plot shifts in a beautiful sequence where Indy gets on a train leaving town. In just a few economical shots, we go from feeling Jones' estrangement from the world --with train smoke billowing in the background as a solemn version of the Raiders March going through what seems to be its last, dying statement-- to the introduction of Mutt Williams, a la Marlon Brando in The Wild One, who glides into the film as if to remind that there's a story to tell. Before Indy takes off on the train, Mutt informs him that an old professor of his (and friend of Jones) is missing. This is the basis of the film's real plot hook.This all sounds like a great set-up, but Koepp sidesteps many of the potential points of drama surrounding Jones' age and his self-realization about never having grown up. Instead, Koepp plunges right into a complicated legend surrounding the crystal skull, the main artifact of interest, mistakenly referred to by George Lucas as the McGuffin. As students of Alfred Hitchcock know, the McGuffin does more then push the plot; it does so for no good reason. The McGuffin actually has no real significance or relevance at all. It's merely the thing everyone is after. Each of the other Indiana Jones films feature a pseudo-religious or supernatural artifact that drives each of their respective stories. Moreover, the first three films concluded with some kind of exposure to the other-worldly power of these artifacts. Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull follows a similar path, but the difference is that the artifact actually is a McGuffin. It doesn't have any significance at all, beyond vanquishing the villain and giving the heroes some place to go. This wouldn't be a problem if the film focused more on style than plot, which the others did. Crystal Skull, however, is weighed down by a mid-section that explains everything and features so much talking about the skull. As a result, no amount of style can maintain the level of interest initiated so brilliantly in the opening 30 minutes of the film. That's not to say it becomes a bore, since there are a few nice flashes through the second act, such as a nice dialogue between Indy and Mutt as they walk through a town in Peru. Even some of the skull jibber-jabber is somewhat interesting early on, as in the nicely staged scene in Professor Oxley's (John Hurt) cell in the town asylum, where Indy and Mutt try to decipher the professor's drawings on the walls and floors.

However, once the skull is discovered, the plot becomes much less interesting. For the first time in the Indiana Jones series, the hokeyness of the plot gets in the way of the real storytelling. I don't want to make it a habit of comparing Crystal Skull to Raiders of the Lost Ark, but consider the "Discovery of the Artifact" scenes from the respective films. In Raiders, Indy and Sallah find the ark in the Well of Souls -- where the jokes about Indy's fear of snakes are actually organic to the narrative. The first shot of the ark itself is one of the film's most memorable moments. As the shiny gold object is removed from the stone chamber, you can feel the power of it. Of course, the concept is absurd, but the brilliance of Raiders of the Lost Ark rests in how effectively in balances that cartoonishness with a real sense of wonder. They are derived from each other. From the moment the ark is discovered, the film's narrative moves to a new stage of intensity, where the stakes are raised, the questions around the ark are still looming, and the mysticism pervading the narrative is taken to new heights. When the film then engages in episodic fist-fighting and truck-chasing, we know that the power of the ark will be unleashed by the time it's done. The action is all anchored by the interest in the ark, and Spielberg was able to comfortably go off on wild tangents of action.

In Crystal Skull the narrative actually loses something when the skull is discovered. The plot susbsequently thickens, as we are reintroduced to Marion (who turns out to be Mutt's mom), as well as the same Russian baddies from the opening scenes. And yet, in spite of all of these plot points coming together and setting up for an action-packed third act, muted interest in the artifact and a convoluted plot distort the enjoyment of seeing all these plot threads in action. I have absolutely no problem with the amount of characters and story threads in the movie; the problem arises out of none of them being terribly interesting. Characters like Irina Spalko (Cate Blanchett), the head villain, and Mac (Ray Winstone), Indy's old friend turned enemy, should be compelling enough to anchor the action, but I found my interest in all of the details and characters fading as the complicated second act unfolded.

Nevertheless, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull manages to pick up steam, starting with the great jungle chase sequence. Beginning as a bickering match between a captive Indy and Marion, this 15-minute action centerpiece of the film is brimming the kind of energy that made the original films so lasting. The action starts with Indy's off-screen punch of a Russian driver. As his body hits the ground on the side of the moving truck --a trademark Indy shot-- John Williams' brass chords essentially announce the onset of an urgent, epic sequence. Once the scene takes flight, we are catapulted into symphony of crashing vehicles, bullets spraying through the jungle greens, and a swashbuckling sword fights on moving cars.

I'll admit that the first time I saw this scene, I had trouble following the action (which is reflective of the overly complicated plot, perhaps). But on second viewing, after realizing that I didn't care about the plot, I opened myself to the sequence as a pure cinematic experience. Interestingly, where the scene doesn't cohere narratively, it does visually. Even if you can't make sense of all the action at a given moment, the flow of the images is masterful. A couple of shots particularly stand out, like when one vehicle flies over an uprooted tree and we see many Russian bodies flailing up into the air just as the vehicle touches down and exits the shot (rather than the shot continuing along with the vehicle). Also, one has to appreciate Spielberg's willingness to hold action shots beyond the norms of contemporary action aesthetics. We've been conditioned to expect edits between shots (usually a string of close-ups) at points of impact, but Spielberg allows the clarity of the action to flow within singular, sustained compositions rather than stringently adhering to traditional montage. When Indy leaps from one truck to the next, the image may not contain the visceral impact of, say, the Bourne films, but we are more entranced by the spectacle of movement. I would have preferred a little less editing on the whole, but Spielberg still manages to orchestrate a wonderful sequence of balletic action that rings very memorable.

On the topic of the visual experience, many critics and audiences have complained that the film is overly reliant on digital effects. There are are certainly sequences that come off as blatantly computer-generated (e.g. certain shots in the duel between Irina and Mutt), but I'm more taken with the successful integrations of digital effects, which are many. Spielberg often employs CGI to lengthen of those sustained shots (mentioned earlier), except he gets more out of them with digital enhancements. He never treats the CG aspects any different from anything else. Perhaps my favorite shot in the whole film occurs during the jungle chase, and features two vehicles emerging from the jungle to approach the cliffs along the river. The composition starts by closely framining Indy and Spalko as the points of focus, but then pulls back to reveal the rocky, jagged cliffs. That it's all accomplished in one shot, with the main characters eventually shrinking out of fucus, is what makes it so simple and perfect. Adding to the visual wonder of the sequence is a shift in musical direction, beginning at the start of the shot, in which John Williams introduces a whole new rhythm on the brass and snares. This all makes for a gorgeous, transient moment of excitement that still dances in my memory. These are the kinds of moments that Spielberg has made a career of conjuring, and yet they are so rarely discussed. Critics would rather seem to discuss the "bigger" moments in Spielberg's library of memorable images.

The remainder of the film is a series of short-stinted action sequences, some of which are rousing and fun, others that are less so. It all leads to a finale that's short on explanation and heavy on supernatural activity. The closing scenes mostly involve the fate of the skull, and work purely as schlocky hocus-pocus fun. Placing them in the context of the building excitement and frustration around a complex plot, the finale represents a weak way to end the movie. Considering the number of potentially interesting characters featured in the climax, it's hard not to see the characters (Mac, Marion, Mutt, Oxley, Irina) as missed opportunities. None of them get the attention they deserve, including Indy. Much of the drama about Indy losing relevance in the world drifts into the background in favor of the standard Spielbergian familial themes that dominate the latter half of the picture. Most of this, even, appears rushed along.

Despite the family dynamics, Crystal Skull is the least involving of all four films, from an emotional standpoint. The glimmers of affection in the opening 30- 40 minutes are all but absent in the second half, when the script has its characters in sand pits, waterfalls, and running through Mayan ruins rather than building anything between them. When the end comes, one's emotional response will likely depend on one's affinity for the previous films, particularly Raiders of the Lost Ark. This strange detachment is reflective of the overall tension of the movie: In trying to be relaxed, Spielberg and co. are at their most boring and ineffective. The real life of the film seems to come where the filmmakers committed less effort to consciously imitating the fun of previous movies. Instead, Crystal Skull introduces a lot of new elements to the series and the character, but never does anything with them. The action moves fast, the plot moves slow, and in the midst of the plot and action, promising thematic ideas are lost in the mix. These include the nation's paranoia that manifests not just in the Russians, but in the increasing prominence nuclear warfare, and suspicions that beings from another world have visited ours. Also tossed aside is Indy's struggle of aging in a changing world, and the implications of his generational divide and its implications for knowledge. These are all hinted at in the film, but it never explores them with enough detail because it's too busy reminiscing.

With Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, Steven Spielberg aimed to make a light, non-threatening, throwback picture. And although he unfortunately largely succeeds at this task, he thankfully contradicts himself with occasional bursts of audiovisual bliss. These portions of bold, unhinged energy are inconsistent, for sure, but they appropriately subvert the atmosphere of comfortable familiarity that Spielberg and Lucas were out to produce. Just like there is never a sense of urgency or threat in the film, Spielberg doesn't seem all that concerned with making a film anywhere near the level of visceral energy as Raiders of the Lost Ark or the almost as brilliant Temple of Doom. Even at it's best, Crystal Skull is tame in comparison to the audacious, and absurdly beautiful imagery of the first two films. The wonder of movement achieved by those films requires a filmmaker to operate completely outside a sense of higher purpose and a feeling of distanced affection for a lovable hero. While Spielberg still loves Indy, he is not willing to give him the kind of film that endeared him so greatly with viewers. As Manohla Dargis noted, Spielberg is not so much bored with this material, but he has clearly moved on from it. He will likely always love the storytelling and ideas that these films represent, but it's obvious that he simply doesn't have the burning desire to make old-fashioned adventures with that kind of fiery vigor that is required of them to be truly memorable in an age of action saturation.

But, to return to the initial observations at the start of this article, there is also something else at play regarding the the reception of the film, and the attitude about Indiana Jones that lead to the film being made in the first place. The nonchalant mood of the movie seems to represent the filmmakers' and audience's self-conscious acknowledgment that Indiana Jones is no longer a hero of the moment, but now a pop culture icon. To see him constricted to a flawed, nearly inconsequential narrative may damage the increasingly positive retrospective of the original three films, which now seem to operate within their own universe and logic. But the underlying tension between the self-conscious approach to the narrative and the real sense of storytelling rhythm that the film only sporadically produces, may be attributed to the notion that both the maker (Spielberg) and the audience, are simply not that interested in the kind of things that Indiana Jones --as a film series and as a cultural idea-- represents, no matter how much we're convinced of that we are.