I was in Northeastern Pennsylvania this past weekend, where in a rustic-looking antique store somewhere in the mountains I discovered a dusty, out-of-print book --at least according to the sign-- on a small table in the corner of the store. It appeared to have been written sometime in the 1970's, by the looks of it, and was called "The Horror People." Like a great deal of film books that I purchased in my teen years, this one is more a pictorial journey through a certain area of cinema, that being horror cinema. Its commentaries are hardly critical, but are instead more of appreciations for various figures (mostly actors) who contributed to the construction of horror as not just a literary genre but a cinematic one as well. I have yet to read the book, but I did have a chance to browse the chapters, which were organized by actor. Just from paging through the book, I was able to tell that it was very imformative from a film history standpoint about the famous horror actors through the mid-70's, with extensive notes on Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, etc.

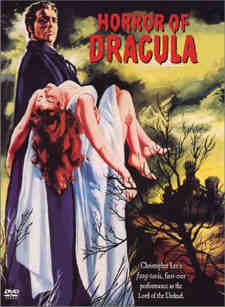

I was in Northeastern Pennsylvania this past weekend, where in a rustic-looking antique store somewhere in the mountains I discovered a dusty, out-of-print book --at least according to the sign-- on a small table in the corner of the store. It appeared to have been written sometime in the 1970's, by the looks of it, and was called "The Horror People." Like a great deal of film books that I purchased in my teen years, this one is more a pictorial journey through a certain area of cinema, that being horror cinema. Its commentaries are hardly critical, but are instead more of appreciations for various figures (mostly actors) who contributed to the construction of horror as not just a literary genre but a cinematic one as well. I have yet to read the book, but I did have a chance to browse the chapters, which were organized by actor. Just from paging through the book, I was able to tell that it was very imformative from a film history standpoint about the famous horror actors through the mid-70's, with extensive notes on Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing, etc. So I decided to buy the book with the hope that I can brush up on my horror genre history. It was also an irresistible buy because, quite simply, it's that time of year. Like many others, October is a special month in my cinematic calendar because it gives me reason to watch as many horror movies as I can. I am not as well read on the genre as others, but I'd like to think I have a fair grasp of this creatively lucrative genre. October is typically a fertile time for critical reflections on horror cinema, from the classic cinema as evoked in "The Horror People" to the slasher flicks of the 80's, and everything in between. On the film blogging circuit, several enthusiastic horror fans have written dedicated space to writing about horror films in the spirit of October. One of the more ambitious of these writers is Rob Humanick, who is currently trudging through a brilliant series entitled the 31 Days of Zombie! on his blog, The Projection Booth. Over the last several weeks, Rob has posted a review of a different horror film each day, and, apart from the freshness of his writing and perspectives, the films he's chosen to write about are incredibly varied. He's written about movies as diverse as Shaun of the Dead, a recent horror comedy, and Sam Raimi's Evil Dead sequels. He has even written about low-grade zombie flicks that I've never even heard of. Elsewhere on the blogging front, Dennis Cozzalio recently offered reflections on his love of horror (particularly in October), as well as a review of an overlooked horror film of the 50's. In his posts, there is an enthusiasm for this style of moviemaking, a nostalgic yearning to understand the ecstacy of turning the lights off, cozying up on the couch with some popcorn, and watching a scary movie, no matter how laughable or truly scary it may be.

Herein lies the wonder of horror as a genre. It's both amazingly versatile as well as inherently nostalgic, limitlessly calling upon audiences' desires to feel fear deep in their blood. From the shadowy masterpieces of the silent era to cheap midnite flicks of the 60's and 70's, cinema has seized horror from the literary world and claimed it as its own. While some would consider horror films to be low-grade trash, especially when compared literary masterworks by Poe, horror occupies is own unique place in cinema. Its finest entries vary from cliche-ridden, self-proclaimed filth to high-class art cinema. If there's anything I've learned while chronicling the various stages of horror cinema through the years, it's that "horror" is a flexible term that doesn't quite function in the same manner as other genre labels like sci-fi, or western. There are countless narrative and stylistic sub-divisions of horror that have spawned over the years, all interesting in their own ways. Moreover, nothing binds horror to certain setting, locales, or even narrative and stylistic approaches. It is a genre of true diversity that represents an overt exploration of the pleasures of spectatorship.

Although most current critics will try to convince you that horror (like westerns, sci-fi, etc.) is dead, I find quite the opposite to be true. While I concede that popular horror cinema is currently stuck in a rut from a mainstream standpoint, especially with the popularity of "torture porn" (which actually seems to be waning), the genre itself is not dead. Within the sub-division of zombie movies, which have been with us for the better part of 40 years, there continue to be new entries that stand out for different reasons. While 28 Weeks Later brings a contemporary flair of style to a relevant story about refugees of a massive virus outbreak, other films simply have fun with the trashiness of horror storytelling. One such example of this is Robert Rodriguez's Planet Terror, which serves up just about every cliche in the book on zombies and still manages to be ceaselessly compelling. While these two disparate films from this past year serve very different purpose and occupy different position in the "zombie canon", they together illustrate the contempoary relevance of horror cinema both in terms of its contemporary relevance and its ability for pure pleasure in the familiarity of movie convention and the explosion of zombie heads. We can know exactly what's going to happen, which ends up becoming part of the fun, or the fear.

Even torture porn is interesting because, like other sub-specialities of horror, it provokes a different reaction and consideration to the question that all horror films beg: What attracts us to being scared, to being on the edge of our seats, biting our fingernails, and squirming in suspense?

The central principle of horror is that it's designed to stir fear within the viewer. But the importance of this genre is not so much its function of creating fear so much as the viewer's desire for that fear. While it's true that it's largest fan base is a rabid core of individuals who live and breathe horror, horror --as a broader concept-- never seems to fall out of the public spotlight, which is staggering when considering the many morphings and permutations of the genre over the years. Just when you think it's gone, dead, or only for the junkies, a horror film will come along that stirs audiences of all ages. The most recent example of this is probably The Blair Witch Project. Although it was almost ten years ago, that film got people talking. Some loved it, and some hated it. Some laughed, while others were kept up at night thinking about its images. This is usually the case with horror movies, whether the threat is paranormal, supernatural, religioso, psychological, doesn't really matter... we seem to crave fear.

The central principle of horror is that it's designed to stir fear within the viewer. But the importance of this genre is not so much its function of creating fear so much as the viewer's desire for that fear. While it's true that it's largest fan base is a rabid core of individuals who live and breathe horror, horror --as a broader concept-- never seems to fall out of the public spotlight, which is staggering when considering the many morphings and permutations of the genre over the years. Just when you think it's gone, dead, or only for the junkies, a horror film will come along that stirs audiences of all ages. The most recent example of this is probably The Blair Witch Project. Although it was almost ten years ago, that film got people talking. Some loved it, and some hated it. Some laughed, while others were kept up at night thinking about its images. This is usually the case with horror movies, whether the threat is paranormal, supernatural, religioso, psychological, doesn't really matter... we seem to crave fear.Most critics or film professors will use the term "identification" when describing the frameworks of narrative and cinema. The reader or viewer is supposed to identify with the central character; the protaganist; the hero. But in the case of horror films, I wonder if this really holds true. Some of the most famous "scary stories" on film, from Psycho to Jaws, do not incline the viewer to identify with the protaganist, but rather the villain. In the case of Psycho, Hitchcock deliberately toys with narrative and cinematic convention by following the central character long after the conventional expository death. She feels incredible guilt throughout the film, like everyone is watching her. That's because we are watching her. The viewer is the ultimate voyeur, which is why so much horror cinema seems to delve into voyeuristic fetishization rather than identifying with a fearful character, like most horror stories. In most horror films, there is usually one character who manages to survive and take out the villain, but that has always felt more like an obligcation on the part of storytellers to tell a tidy story and let the hero win. In reality, the most successful horror stories on film force the audience to identify with a voyeuristic, predatory killer, whether that's a 25-foot shark, stalking swimming woman from the depths of the sea, a psychotic motel owner who watches his residents shower through holes in the wall, or a rogue alien, stalking members of a ship in deep outer space.

The most overt example of this form of identification is the "killer vision", used extensively in films like Jaws and Halloween. Beyond these obvious stylistic touches, there is something larger going on in horror cinema that deserves serious consideration, because through horror films we see why cinema differs so greatly from other storytelling media. Showcasing brutal acts of violence, twisted feelings of surveillance, and a impulse for penetrating skin/bodies, horror films seem to tap into something deep within the collective psyche. In its focus on trauma, violence, bodies, and skin, the genre calls to mind several key issues with regard to spectatorship and the perception and interpretation of narrative through images. Apart from latent cultural perspectives on gender, race, class, and narrative, which manifest in a variety of archetypical images of force, power, and domination, the crisis of identification evoked in horror movies almost forces one to consider the relationship of the viewer and the image in a new light. In short, horror cinema is a microcosm for cinema itself.

The most overt example of this form of identification is the "killer vision", used extensively in films like Jaws and Halloween. Beyond these obvious stylistic touches, there is something larger going on in horror cinema that deserves serious consideration, because through horror films we see why cinema differs so greatly from other storytelling media. Showcasing brutal acts of violence, twisted feelings of surveillance, and a impulse for penetrating skin/bodies, horror films seem to tap into something deep within the collective psyche. In its focus on trauma, violence, bodies, and skin, the genre calls to mind several key issues with regard to spectatorship and the perception and interpretation of narrative through images. Apart from latent cultural perspectives on gender, race, class, and narrative, which manifest in a variety of archetypical images of force, power, and domination, the crisis of identification evoked in horror movies almost forces one to consider the relationship of the viewer and the image in a new light. In short, horror cinema is a microcosm for cinema itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment