One of the running themes on Jim Emerson's scanners blog over the last year (roughly) is contrarianism as it relates to film criticism. Starting with a string of posts about Martin Scorsese's pedantic and shallow Oscar winner, The Departed, and various other things, Jim wrote piece after piece examining the idea of contrarianism. The discussions that resulted were enormous and rich, which is (I would guess) partly why he felt so inspired to continue writing about it. Eventually, he organized a contrarian blog-a-thon, which turned out to be quite a large event in the film blogging circuit, bringing in a number of contrarian perspectives on film, culture, and contrarianism. Although I would have loved to have delved more into my own contrarian passions, of which I have many, I opted to write more broadly about guilty pleasures. (My long gestating contrarian perspective of Frank Marshall's brilliant 1995 film Congo is still in development, and will see the light of day on this blog sometime in the hopefully near future. I promise.) But I love to relish in contrarian viewpoints, especially on taboo subjects like critically panned movies.

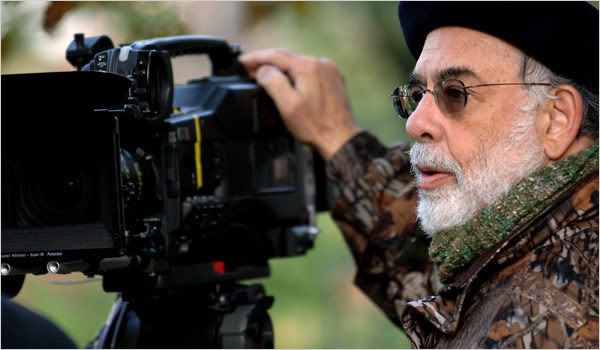

One of the running themes on Jim Emerson's scanners blog over the last year (roughly) is contrarianism as it relates to film criticism. Starting with a string of posts about Martin Scorsese's pedantic and shallow Oscar winner, The Departed, and various other things, Jim wrote piece after piece examining the idea of contrarianism. The discussions that resulted were enormous and rich, which is (I would guess) partly why he felt so inspired to continue writing about it. Eventually, he organized a contrarian blog-a-thon, which turned out to be quite a large event in the film blogging circuit, bringing in a number of contrarian perspectives on film, culture, and contrarianism. Although I would have loved to have delved more into my own contrarian passions, of which I have many, I opted to write more broadly about guilty pleasures. (My long gestating contrarian perspective of Frank Marshall's brilliant 1995 film Congo is still in development, and will see the light of day on this blog sometime in the hopefully near future. I promise.) But I love to relish in contrarian viewpoints, especially on taboo subjects like critically panned movies.One recent example of how the critics turn against their once-darling filmmakers is Youth Without Youth, Francis Ford Coppola's long-awaited return to directing. I remember eagerly anticipating this film when I read about it last year. I was disheartened, however, to learn that most critics ripped the film -- it scored a poor 28 percent on the Tomatometer -- and its maker for being overly pretentious, heavy-handed, and condescending. Francis Ford Coppola, it seems, has fallen out of graces with the critics who championed him as the wonderboy of cinema 35 years ago. Amazingly, much of the criticism of the film echoed the same rhetoric about other supposedly "once great" auteurs, namely Woody Allen, whose recent films are unfairly simplified and situated within the "What Happend to Woody?" narrative to a sickening degree. Although Youth Without Youth is the first movie to be subject to such negative judgment, I fear that Coppola may be doomed to the same fate with critics, many of whom are so baffled that a filmmaker dares to offer something different from her/his previous work that they choose to deride the art. In trying to be contrarian and cutting edge -- like most critics are painted -- critics actually draw themselves as the boring community of homogenized writing styles they so adamantly reject.

Based on the skewering criticism, it came as no surprise in its very limited release that was quickly "shown the door" at the cinema arthouses last December, when films like There Will Be Blood, Persepolis, and various others were competing for cinema goers' attention. In the blink of an eye, it seems, Youth Without Youth was gone, never to be heard from again like so many interesting looking films as awards season reared its head and started cutting down films to the small number that will be admitted into contemporary critical canon. It should be noted that films admitted to canon now often fail to resonate as much as films that were ignored in-the-moment, but over time were more memorable.

Based on the skewering criticism, it came as no surprise in its very limited release that was quickly "shown the door" at the cinema arthouses last December, when films like There Will Be Blood, Persepolis, and various others were competing for cinema goers' attention. In the blink of an eye, it seems, Youth Without Youth was gone, never to be heard from again like so many interesting looking films as awards season reared its head and started cutting down films to the small number that will be admitted into contemporary critical canon. It should be noted that films admitted to canon now often fail to resonate as much as films that were ignored in-the-moment, but over time were more memorable.I discussed the danger of awards season discourse in a recent entry, in which I highlighted the importance of critics who were willing to swim against the current and talk about films no one else was talking about during awards season, such as David Cronenberg's mesmerizing, every-bit-as-good-as-No Country For Old Men film, Eastern Promises. But I admire just as much the critic who admirably discusses, and demands that we pay attention films that not only get forgotten, but which are disparaged and then forgotten, like Youth Without Youth.

Larry Aydlette is one of these critics. His seemingly bold take on the film, whether you agree or not, is utterly necessary at a time when so much criticism appears the same, not just in tone and structure, but in viewpoint too. His review of Youth Without Youth is inspiring, and should make and cinephile or critic want to see the film. Given that it would be impossible for any critic defending this film not to position her or himself as a "defender" of it, Aydlette takes on these criticisms head-on, and is baffled with the strangely uniform and predictable critical response to the film.

"I was completely mesmerized by Francis Ford Coppola's “Youth Without Youth.” If I had seen it last year, it would easily have made my Top 5 films of 2007. Where are all the cinephiles on this one? Why aren’t they supporting this legendary filmmaker? Isn't this what bloggers say they want more of: Independent movies with intelligence and storytelling and heart? I think that the failure here is not Coppola’s, but ours.

"Youth Without Youth” is told with passion and a love of a cinema that no longer exists. It’s the best movie Francis Ford Coppola has made since “Apocalypse Now.” Coppola has long promised to return to smaller, artier, more experimental films. This isn’t exactly experimental; it’s very soulful and old-fashioned. But in today’s film language, that’s downright radical. “Youth Without Youth” is one from the heart. Go see it."

Simple, direct, and somewhat fiery. It's perfect. I should probably disclose that I haven't seen Youth Without Youth, but whether I've seen it or not is really the point. The reason this is important is because it reminds of how much critics actually become figures predictable sameness in their attempts to be cultural contrarians. It's firstly interesting that so many directors in their later years tend to be unfairly judged in a negative manner, as if critics recognize that they perhaps gave a filmmaker too much credit for her/his classics or masterpieces and are now making up for it. It is quite fascinating, though, to examine critical trends, specifically how certain filmmaking styles and aesthetic conventions suddenly become taboo, such as mise-en-scene and classically-influenced cinematography.

Simple, direct, and somewhat fiery. It's perfect. I should probably disclose that I haven't seen Youth Without Youth, but whether I've seen it or not is really the point. The reason this is important is because it reminds of how much critics actually become figures predictable sameness in their attempts to be cultural contrarians. It's firstly interesting that so many directors in their later years tend to be unfairly judged in a negative manner, as if critics recognize that they perhaps gave a filmmaker too much credit for her/his classics or masterpieces and are now making up for it. It is quite fascinating, though, to examine critical trends, specifically how certain filmmaking styles and aesthetic conventions suddenly become taboo, such as mise-en-scene and classically-influenced cinematography. But in a broader sense, I wonder if critics are losing touch with what it means to see films and write about them, and whether their sense of history contorts their understanding of contemporary cinema. Do we need a proverbial slap in the face to pull ourselves away of the same-old, boring conventions of predictable contrarianism? And at what point does being contrarian actually become the very act of sameness that contrarianism sought to reject in the first place? But I suppose the bigger question to come out of this is whether there is any way of shifting the critical dialogue away from the dominant binary approach of majority/minority and injecting it with the same amount of nuance that complex films demand?

5 comments:

I believe that all of this is the reason that many critics, notably Pauline Kael, had problems with the auteur theory back in its infancy. Though I have my problems with Kael I tend to agree with her in her arguments against Sarris.

I believe works of art should be judged on their own merits, not by who did them. I believe who did them is vitally important to understanding the artist but unimportant in judging the work. Thus, knowledge of Woody Allen's personal travails, tastes and experiences enrich our understanding of Deconstructing Harry and it is a worthwhile analytical venture to deconstruct Woody in the face of the film for deeper understanding. But the film itself is what it is and should be judged on its merits as a stand-alone work of art, free of a creator, suspended alone in the ether.

I have a love/hate relationship with Auteurism. The love part cherishes gaining deeper insight into a film's meaning in relation to its creator, the hate part finds it a cheap critical rating system. It smacks of "Brand-Name" consumerism. The idea that the label on the jeans make the jeans better. And it does influence critical thought. Last year when the French wine critics were embarrassed by the scientific study of their judging methods I was reminded of film criticism (In case you missed it a study was conducted with 41 wine experts in France. The wines were doctored - literally in some cases serving a white warm with red dye to pass it off as a merlot - And it worked!!! to other cases where when the experts were told a certain wine was by a highly respected vineyard they rated it much higher than they had rated it earlier in blind tests and vice versa when told the vineyard was a little respected one. The experts were very upset after the study was released and came up with the usual excuses - "I knew what they were doing but I didn't want to make waves" - uh huh). I thought to myself, critics do that. Show them a movie with no credits and no advance knowledge of who did it and the reactions would probably be quite different at times.

I think one of the best verifiers of this is the independent film done by the first time filmmaker. In many cases the critical reaction to a first time filmmaker (Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson, Robert Rodriguez) is congenial and usually based on the merit of the film alone. The critics have no choice. There is NO HISTORY.

Then flash ahead to Darjeeling Limited, There Will Be Blood, Grindhouse and suddenly every review is peppered with references to previous films; how it didn't hold up to prior efforts; how it employs the same "tricks"; how it is or isn't whatever the hell the critic wants to assign it based on everything that came before.

And it will keep happening because the history only grows which is why a director not only has his own history used against him but the entire history of cinema as well, i.e. does his latest horror flick "re-invent" the genre, etc.

As it snowballs forward into time do not expect more of the same.

Expect MUCH, MUCH MORE of the same.

Thanks for your insights, Jonathan! I think you're absolutely right about the dangers of auteurism. It's something I deal with myself quite a bit. And it's very difficult. Ultimately, it's impossible not to recognize certain pieces of information about a film, whether that's before or after we see it. When we can associate certain styles or conventions with particular filmmakers, we are immediately positioning their film within a particular interpretive schema, one that can actually take away from actually seeing the film.

At the same time, films don't exist in a vacuum. The "pure" film experience is not possible. That which we consider fresh is only deemed so because we have exposed ourselves or been exposed to particular ways of doing things. So that when something does not accord to that pattern, we see it as "different" -- that can be "good" or "bad" depending on other circumstances.

Much of these ideas can be traced back to standpoint epistemology and philosophy, although standpoint theory is more concerned with matters of class, linguistic, and other social structures.

Cinema is perhaps something different; yet we still project age-old social structures onto cinema and employ tired methods of truth-claims and aesthetic evaluation to try to "understand" or "interpret" art. It's a shame really, that we don't push or challenge ourselves more in our methods. Critics are often just as predictabble as the films they judge.

Real criticism is not about these things at all, but is instead about the discovery of thought and knowledge. In cinema, images become. In criticism, concepts become.

Ted, thanks for the kind words. I hardly thought my brief write-up of the film was fiery or particularly deep. I just enjoyed the film, and I hope more people give it a chance. One other thought: More and more often you see deeper retrospectives of the later years of an artist, be it Picasso or John Ford. In almost every case, the critics at the time dismissed these later works, only to see them come back in vogue with the passage of time.

Larry,

That your piece was a simple "I liked it," was why I found it so refreshing. You didn't launch a full-scale defense of the film, but instead simply turned the issue around on those who so easily dismissed it, and asked, "where were you, cinephiles?"

It's a potent question, probably because it's so blunt. With some filmmakers, everything they touch is critical gold for a period, but this is usually followed by a period (later in their careers) in which there's nothing they can do to achieve any kind of relevance, from critical evaluations at least.

But it's interesting that you point out that many directors' later work, although disliked at the time, are analyzed most after the fact. As you point out, this is a very common trend, and it seems less about the filmmakers themselves than it does about how critics understand auteurism and how film criticism --whether its individual participants are aware of it-- enacts a love-hate pattern with a great deal of filmmakers.

"where were you, cinephiles?"

Just so Larry knows, I was in the bathroom.

Sorry.

Post a Comment