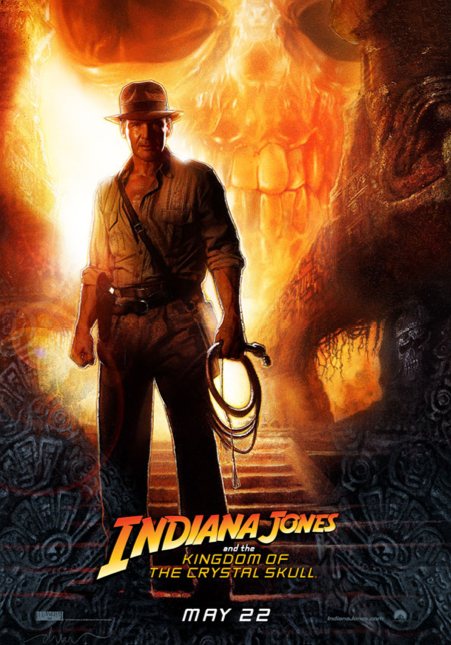

Now that Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is here, we may soon finally catch a break from the film's marketing machine. Seeing Harrison Ford's face plastered over everything from buses to candy bar was cute for a while, but in recent weeks the saturation of Indiana Jones has reached a frightening high.

Now that Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull is here, we may soon finally catch a break from the film's marketing machine. Seeing Harrison Ford's face plastered over everything from buses to candy bar was cute for a while, but in recent weeks the saturation of Indiana Jones has reached a frightening high. I expected this with the new Star Wars trilogy, since the 20 years between Return of the Jedi and The Phantom Menace have shown that Star Wars was not about the movies or the storytelling, but instead about the consumer product, as evident in the resulting movies. But with Indiana Jones, the films have always stood on their own, as big budget, old-fashioned Hollywood entertainments. The films weren't advertised to death, wrapped in plastic, or spewing out products in every kids market. They achieved their notoriety in American culture because of their charm and style; you know... things internal to the movies themselves. Now that Indy is everywhere, though, my spirits are somewhat dampened. I am looking forward to the film as much as any die-hard Indy fan, having grown up watching the films, but I am more than a little turned off by the media blitz, to be honest.

The (marginally positive) reviews are piling in now, and soon I will have finally seen the movie. But when I sit down in the theater tomorrow morning, I don't think I'll so easily be able to divorce myself from the assault of advertising images I've seen in the past weeks and months. And it will have a bearing on how I see the movie.

I'll offer my thoughts on the actual movie by Thursday evening or Friday, but for now I'm interested in where the many symbols and images of Indiana Jones converge. The two that most interest me are: Indiana Jones, as both a character and a popular movie franchise, and also, Indiana Jones as a successful business model and marketing tool. This may be hard for me, due to my previously established connection to the original three Indy films. But my allegiance to those movies (and to Raiders of the Lost Ark, especially) may actually make for an interesting exploration of the cultural status of Indiana Jones, and what its popularity indicates and reflects about American culture.

My interest in this discussion began when I read Carrie Rickey's refreshingly negative perspective on Dr. Jones, which appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer only a couple of days ago. In her article, she refers to the films as sexist, and their hero a colonialist. These are hefty claims that she couldn't possibly justify in one article; but that's not really the point of the article. With all the sensational media buzz about Jones, it's a breath of fresh air to see a prominent film critic voice her near disdain for the franchise, deeming it an masculinist and nationalist fable. I'm not sure I agree with all of Rickey's claims, but I applaud her willingness to raise them. Her piece represents the best thing I've read about Indiana Jones in the last six months, and it got me to consider these films in a different light. While I have been slowly realizing over the years how many of my beloved movies as a kid tend to represent dominant masculinity and American domination, I've resisted situating the Jones films in this discussion, mostly due to my love of the first film.

I try to avoid being too Jungian with movies, but it's hard to deny the allusions in the Indiana Jones series. Jones himself represents the ultimate masculinist in the tradition of James Bond, with a new girl in each flick, none of whose combined screen time in all three films add up to his time in one film. Moreover, the films are made in the male-centric Hollywood tradition, where the men are always heroes, and the women damsels in distress. But besides the issues of gender in these movies, there are also some trouble nationalistic conflicts as well. One could say that in the movies where Jones battles the Nazis, that he represents America; a sometimes reckless, but ultimately pure hero who comes just at the right moment to save the day, and bringing peace to the world by stopping the Nazis. And then, in the Temple of Doom he arrives (by mistake) in poverty-stricken India, where primitive villagers need the white man to bring prosperity and purpose to their lives again.

I try to avoid being too Jungian with movies, but it's hard to deny the allusions in the Indiana Jones series. Jones himself represents the ultimate masculinist in the tradition of James Bond, with a new girl in each flick, none of whose combined screen time in all three films add up to his time in one film. Moreover, the films are made in the male-centric Hollywood tradition, where the men are always heroes, and the women damsels in distress. But besides the issues of gender in these movies, there are also some trouble nationalistic conflicts as well. One could say that in the movies where Jones battles the Nazis, that he represents America; a sometimes reckless, but ultimately pure hero who comes just at the right moment to save the day, and bringing peace to the world by stopping the Nazis. And then, in the Temple of Doom he arrives (by mistake) in poverty-stricken India, where primitive villagers need the white man to bring prosperity and purpose to their lives again. As I said before, these connections are by no means definitive, or even substantive. But they are troubling in their bluntness. And now that Indiana Jones is invading all areas of commercial America, it's hard not to consider the implications of these notions for American consumer culture, where, despite a proliferation of media and information, many age-old assumptions and stereotypes about gender, race, and class are intensified.

The other side to Rickey's argument, one for which I hold considerably less optimism, is her assessment of the movies' effect on Hollywood action aesthetics. She cites David Bordwell in a concerted effort to demonstrate Steven Spielberg's ushering in of contemporary visual styles of shortened shot lengths and attention-deficit cinema. There's certainly no denying that Raiders of the Lost Ark boasted a considerably reduced average shot length than Spielberg's previous pictures, it's important to note that in comparison to most other motion-oriented action films, 4.5 seconds per shot (which was that of Raiders) is quite long.

Where we're on shaky ground here is in the potential confusion of forms of content and expression. Spielberg can certainly be credited (along with George Lucas) to invigorating Hollywood cinema with speed and motion, he did not do so with heavier editing and more close-ups. He did it by mastering classical styles, and achieving a maximum effect of impact and movement on screen. Say what you will about what Raiders of the Lost Ark signifies as a narrative or cultural artifact, it employed a thoroughly traditional visual style to create some of the most amazing sequences. Indict Spielberg for a hundred other things, but it would be foolish to argue from a pure formal standpoint that Spielberg ushered in a shorter attention span for cinematic consumption. He may have done so in his synergistic approach to Hollywood moviemaking and marketing, or in building on traditional racial and gender stereotypes, but his aesthetic is grounded firmly in a rich classical tradition. If it appears intensified, it's because he imbued that tradition with greater impact and motion, staging more impossible sequences and only cutting for impact.

Interestingly, Spielberg's Indy films were amazingly influential on Hollywood moviemaking, but in the worst of ways. Because while he stayed true to a traditional aesthetic design, his imitators took his ideological direction and pushed it forward by intensifying those aesthetics. Hence, shot times have diminished, and the average moviegoer's sensibilities are skewed to favor quick flashes of sight and sound rather than formal appreciation of a moving image. Subsequently, movies have been made with this kind of consumption in mind, and fewer filmmakers working on a bigger budget have a sense of the craft of filmmaking anymore. But Spielberg has always honored the rick cinematic tradition of moving images, and it's why his work is significant as not only that of a icon of economic synergy, but also of real cinematic artistry. He may be a slave to American capitalism, but his aesthetics are honest, and therefore he demands attention and consideration.

So as the dialogue continues about the cultural significance of Indiana Jones and the implications of its mass distribution in a globalized (although some would say Americanized) market, there is only one thing left to discuss: the movie. Lucas' Star Wars flicks suffered immensely from being placed on the back burner of the commodity machine. Soon we'll see if Spielberg has followed the same path, and in doing sacrificing the one aspect of his commercial filmmaking that makes him interesting: the filmmaking.

[As I noted earlier, I will be seeing the film early tomorrow morning, and will post a review of the film on its own terms (as much as I can, at least) shortly thereafter. After this discussion of the movie as a piece of pop pulp, I will do everything I can to keep my focuses on the movie itself in the review.]

[As I noted earlier, I will be seeing the film early tomorrow morning, and will post a review of the film on its own terms (as much as I can, at least) shortly thereafter. After this discussion of the movie as a piece of pop pulp, I will do everything I can to keep my focuses on the movie itself in the review.]

3 comments:

Good luck watching the movie. Good, good luck.

I'm interested in hearing more about the traditional forms that Spielberg used.

The latest movie definitely veers away from that, opting for the fast edit, short take style that seems so prevalent today.

I got to thinking about the marketing overload of "Indy" while shopping for groceries and seeing just how many products had The Hat printed on them. My question is: it's been almost TWENTY YEARS since the last Jones adventure, do kids really know about Indy or care that he's in a new movie? That's why I'm not sure if it will be a blockbuster or not, just can't imagine too many from the Harry Potter Generation lining up for tickets.

I hope this movie is all what's it hyped up to be. Enjoy! =:0)

Post a Comment